The phone rang just as I had finished the interview with the Canadian soprano Sharon Azrieli and was on my way home. A young representative of the Mathias Corvinus College[1] was looking for me – I had been recommended to him as the right person to help a well-known musicologist from England find his Jewish roots in Transylvania. I replied that I’m sorry, I’m not a historian and I don’t have the necessary knowledge to discover Transylvanian Jewish roots, at most I can recommend the right people who could help him.

– Please, don’t let us down. The professor is coming to Cluj tomorrow, his schedule is already fixed and the meeting with you is on the schedule.”

I accepted.

The next day, at lunch, I was sitting on a terrace in the heart of Cluj, opposite Michael Spitzer – none other than the author of The Musical Human[2], a relatively young man, with bright eyes and a friendly smile. He arrived at the meeting after a tour of the most important historical sites of the city.

– Have you seen the Memorial Monument to the Holocaust Martyrs? – I asked him.

After his affirmative answer, I explained the meaning of the five uneven granite columns. They represent the groups of five inmates on the Appelplatz. The strongest stood at the edges to support the weakest in the middle, who could barely stand on their feet.

– This is how my mother would have been protected by the two aunts, Regi and Manci, with whom she survived – Michael Spitzer told me.

– Was your mother deported? Where from?

– From Cluj

– How old was she?

– 15.

– And what did she tell you?

– Nothing.

It wouldn’t be the first time that a survivor avoids telling the children about what he endured in the camp… But absolutely nothing??

– Is your mother still alive? Where is she?

– No. She died at my birth.

– And what do you know about her?

– Very little. Her name was Lili Rosenfeld. She was deported from Cluj at the age of 15. She was the only survivor in her family. Immediately after the war she met my father, they got married and went to Palestine.

Then Michael Spitzer told me briefly what he knew about his mother, Lili Rosenfeld.

I managed to find out that my mother was not born in Cluj, but in a nearby village, her mother’s last name was Rosenberg…

Lili was released together with her aunts, Regi and Manci, and they arrived together in Salzburg, where she met my father. He proposed to her at the Mozarteum, something that seemed to me an omen. My father János (Yoel, John) Spitzer was born in Püspökladány, in the family of the district doctor. He attended high school in Debrecen and studied Medicine in Budapest. From August 1944 until the liberation of Budapest, he was hidden by a Croatian shopkeeper. After the marriage, my parents went to Milan, where they waited two years before leaving for Palestine. Finally, they arrived in Cyprus and then in Israel. They settled in a kibbutz established by Hungarian Jews. Their first son [Benjamin] lost his life in the kibbutz, following a train accident. The second, Gabriel, was born in 1950. In 1959 my father went to work in Nigeria, a country with which Israel had quite close economic ties. My mother followed a few months later. I was a late child, I was born in 1966, 16 years after my brother. Unfortunately, my mother passed away due to a severe post-partum haemorrhage, because the hospital in Ibadan did not have the necessary medicines to save her life. Lili died exactly on my birthday. Her lifeless body was put on a plane and taken to Israel where she was buried. I was nursed by a Nigerian nanny. After a while, my father married an English woman. I lived in Israel until I was seven years old. In 1973, after the Yom Kippur War, we settled in England…

Lili Rosenfeld died without even seeing her son, let alone telling him about her family… Michael Spitzer knew nothing about his maternal grandparents who perished in the Holocaust, about his mother’s childhood and adolescence. Now he was in Cluj for the first time, just passing through, and he wanted to know something about his roots. The Mathias Corvinus College had asked me to help him…

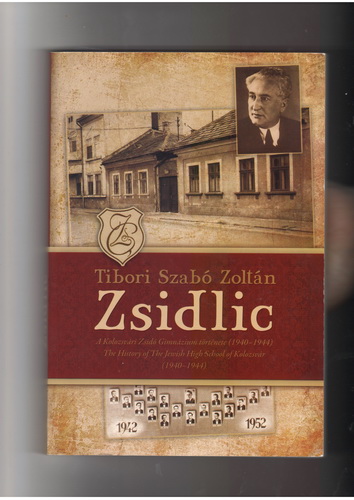

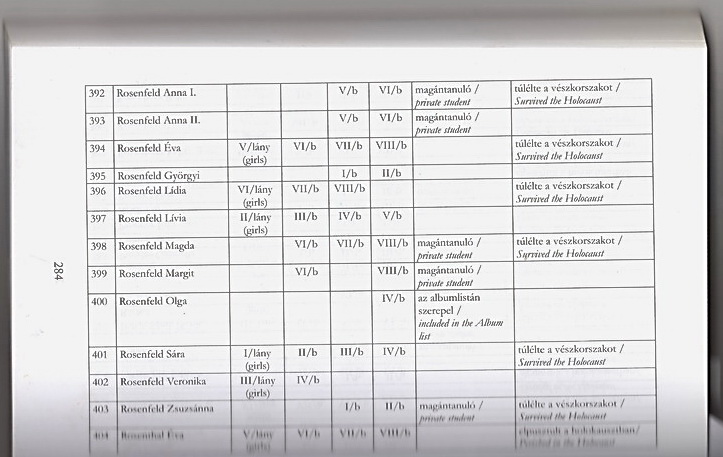

Lili Rosenfeld was 15 years old at the time of deportation. If she was a student at the Jewish High School in Cluj[3], there would be a chance to find out more about her. I left Michael Spitzer and ran home, took out the monograph of the Jewish High School (Zsidlic in student slang) [4] in Cluj, read the list of students and at position 397 I found her: Rosenfeld Livia.

In the school year 1940/41 she was in the 2nd grade of high school, and in the last school year, before the deportation 1943/1944 she was in the 5th grade B. The last column of the list, which contained the information related to the Holocaust, was empty, those who drew it up did not know that she survived.

Livia (Lili) Rosenfeld was in the same class with two good friends of my mother, both alive: Judith Mureşan (née Kertész)[5] who lives in Cluj and Dora Sitnovitzer (née Hecht) who lives in Tel Aviv. I called Judith and asked her if she remembered Lili Rosenfeld.

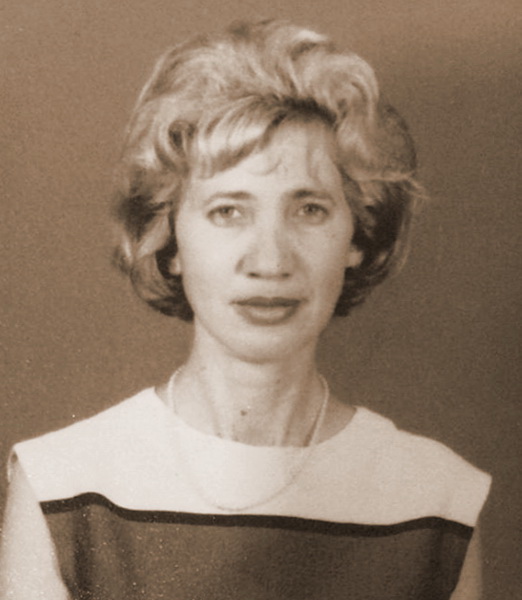

– She was a blonde, delicate, polite, and quiet girl. She appears in my class photos. Unfortunately, she did not survive the deportation.

– Yes, she survived, but she died after the birth of her youngest son, the musicologist Michael Spitzer from England. He is in Cluj for a day and he would like to know what his mother was like as a child. Can you see him?

– I thought Lili died in the camp! Incredible! She survived and none of her colleagues knew… Of course, I will meet her son!

I was so agitated that I could no longer wait to meet Judith. I searched the Baabel Archive for her article about the Jewish High School[6] and sent the class photo on WhatsApp to Krisztina Farkas, the Mathias Corvin College representative who accompanied Michael.

Lili was the only blonde student in the photo. A minute later came the answer:

– It is her! Michael recognized her.

The meeting between Judith Mureşan and Michael Spitzer was emotional! Both of them had tears in their eyes. She, because she had found out (after almost 80 years) that Lili had survived the Holocaust, but had died young, and he, because Judith’s memories (pale as they were) revived something from his mother’s childhood and adolescence. Michael called his family and made the introductions on WhatsApp. Indeed, as he had told us, his daughters looked like Lili.

Michael would have wanted to know more about his mother and her family, but Lili and Judith had not been in the same circle of friends.

– I don’t remember much about Lili. In the photo she is standing next to Dora. As far as I remember, they were friends, you should talk to her too.

I immediately called Dora Sitnovitzer, right there in the restaurant. To our great surprise, she had met Lili Rosenfeld in Israel in the 1950s. She knew her son, Gabi, and she had been to her funeral… Moved, she promised to put her memories in order.

The next morning Michael left for Târgu Mures. On Sunday he returned to Cluj and had a few hours before boarding the flight to Liverpool.

I returned home late at night, thinking about Lili Rosenfeld, about the fact that her survival was not mentioned in the high school monograph. I remembered that the first world meeting of surviving high school classmates took place in 1980, in Cluj. As Zoltán Tibori Szabó points out in his monograph: “Shockingly enough, 35 years had to pass by before 1940-1944 teachers and students of the Jewish Highschool felt the need to meet not only in small gatherings but also in an organized form. The planning was painstaking and required a substantial international effort. The blast of the Nazi absolutism that shattered the school also dispersed in remains across the Globe. Tracing their addresses was possible only through difficult, small-paced efforts.”

In 1979, when the organization of the meeting began, Lili Rosenfeld had been dead for 13 years… Who would have remembered her?

I wondered if after being released from the camp she had gone straight to Austria or had returned home first, as most of the survivors did, wanting to know what had become of their families. After learning the terrible truth, many left Transylvania.

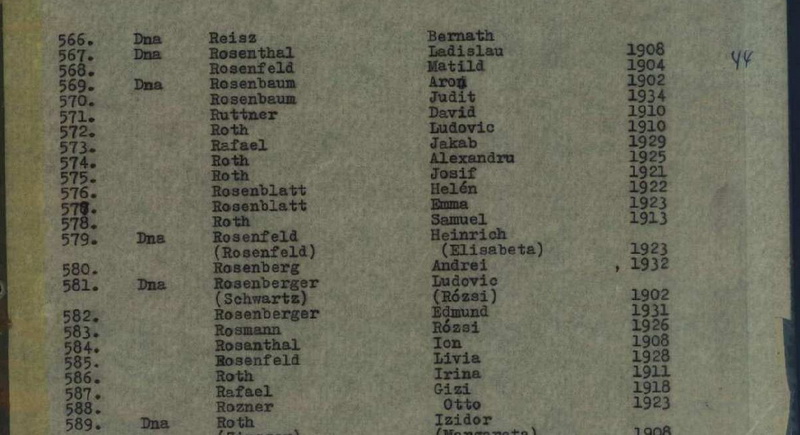

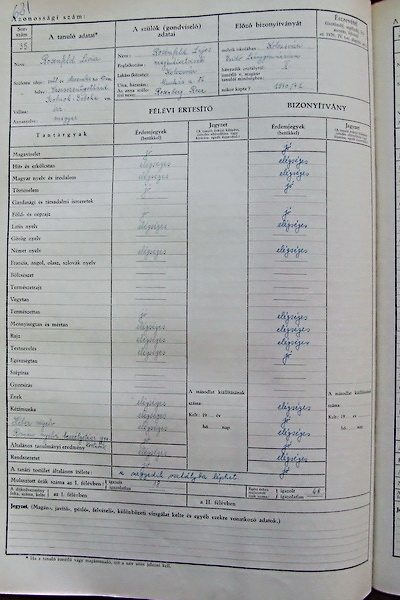

I was going to find out the answer from Attila Gidó’s book 20000 names[7], in which Livia Rosenfeld’s name appears twice (from different sources). I contacted the author and he sent me the list of deportees who returned to Cluj in July 1945 and another essential document: the transcript from the Jewish High School, from the school year 1940/41, where the place of birth, Vasasszentgothárd commune (the current Sucutard, Cluj county), parents’ names (Lajos Rosenfeld and Roza Rosenberg) and their Cluj address (Munkás street no. 86). Moreover, Attila Gidó had also been the source of the little information that Michael Spitzer had about his mother.

From The Geographical Encyclopedia of the Holocaust in Northern Transylvania[8], I learned that the family of the merchant Jakab Rosenberg (Lili’s mother’s family) had lived in Sucutard.

The essential additions for a first sketch of Lili Rosenfeld’s childhood would come from Dora Sitnovitzer who had known Lili since kindergarten and the Orthodox Elementary School. Dora lived on Bástya Street (currently Daicoviciu), near Carolina Square (currently Museum Square).

– There we both learned to ride a bicycle, she remembers. Lili’s father worked at the gas station in Széchényi Square (currently Mihai Viteazul) and we often went to his place. He would give us money to buy ice cream from the stall in the market. Sometimes Lili’s older brother came with us.

I was lucky and in two days I was able to gather some information. On Sunday, Michael Spitzer returned from Târgu Mureş with many pleasant impressions from the event organized by the Mathias Corvinus College. I had about three hours at my disposal. I proposed a trip to the streets that Lili Rosenfeld had passed in her childhood and adolescence.

Unfortunately, Munkás street (now Muncitorilor) has changed completely. In the 1980s, all the houses were demolished, and blocks of flats were built. Number 86 doesn’t even exist, so there was no point in going there.

We started towards the Old Center, we passed the former house where Dora used to live and we stopped in Piata Muzeului (formerly Carolina) where the two little girls (joined in the class photo) learned to ride a bicycle.

We headed to Mihai Viteazul Square (formerly Széchényi) where the gas station used to stand, where Dora’s father had worked, and where the ice cream stall would have been. Then we went to Iaşilor Street (formerly Szamos), where the Jewish High School had operated from 1940-1944. Now the house is inhabited by private individuals. Michael called and a kind lady let us see the old school building.

Lili Rosenfeld survived, the blonde and delicate little girl turned into a beautiful woman who had several good years, got to travel, to live in Nigeria where she frequented the best society…

She died young, giving birth to her son who would become a musicologist, one of the most renowned researchers of Beethoven and the author of an impressive work of synthesis: The Musical Human.

Michael Spitzer, born in 1966, is also part of the G2 generation, marked by the trauma of the Holocaust.

– My parents were originally from Transylvania and Hungary, but I don’t know either the places or the language. I was born in Nigeria, but I am not African, I spent my early years in Israel, but I cannot identify with that country, nor with the Jews, nor with England, where I have lived since childhood. Perhaps that has changed since becoming a father, as I am linked to Liverpool through my children. My home was and remains music.

For Michael Spitzer, the visit to Cluj was a first step in finding his roots. There are still many questions that – hopefully – can be answered by researching the archives in Sucutard and beyond. I hope he will soon return to this city that still preserves the footsteps of his mother, Lili Rosenfeld, the blond and delicate girl who lived in Cluj, before the Holocaust.

Andrea Ghiţă

(The English version was revised by Hava Oren)

(Photos by Michael Spitzer and Andrea Ghiţă)

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathias_Corvinus_Collegium

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Spitzer; https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/53138191

[3] The Jewish High School in Cluj was established in 1940, when Jewish students and teachers were eliminated from public schools. The Jewish High School functioned until May 1944 when the students and teachers were deported to Auschwitz. The overwhelming majority perished in the nazi concentration camps.

[4] Tibori Szabó Zoltán, Zsidlic, Ed. Mega, 2012, Cluj

[5] Judith Mureşan published several articles in Baabel

[6] Judith Mureşan, Ce urme lasă studiile (2). https://baabel.ro/2020/12/ce-urme-lasa-studiile-2/

[7] Gido, Attila, 20000 de nume, evidenţa deportaţilor din Transilvania de Nord rămaşi în viaţă, Institutul de Studiere a Problemelor Minorităţilor Naţionale, Cluj, 2020

[8] Braham, Randolph L., Tibori Szabó, Z, Enciclopedia Geografică a Holocaustului din Transilvania de Nord, ed. Cartier, Chişinău, 2019

4 Comments

Although I’ve just descovered the article, I still want to express my admiration for the empathic and thorow way Mrs Ghita invested her effort to help but still let us take part in this adventure.

Great example of investigative journalism. It conveys emotions and empathy, well beyond the dry findings. It should be of great interest and highly relevant to Baabel’s readers and not only. Andrea managed to describe the search for roots in a way that truly touches the reader. Many of Baabel’s readers and beyond would identify with Michael Spitzer’s feelings of not belonging and “feeling at home only in music” , There are many more among the assimilated Jews, who don’t believe in any particular continuity with their ancestor’s past, but at the same time , would like to learn more and understand more about their own past. This is a niche which Andrea identified and described in a fresh, thriller-like style, inviting the reader to learn more about it. Bravo, Andrea!

Thanks for this comment. I guess I got lucky. I would like to be able to discover the footsteps of other Jewish children from Cluj, who perished in the Holocaust together with their families and nobody knows anything about them.

Excellent, well written story! Great job Andrea!